Hugh Philp

(1782-1856)

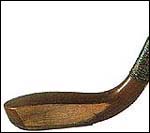

Long Spoon

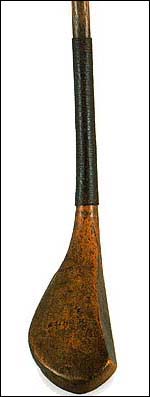

Long Spoon

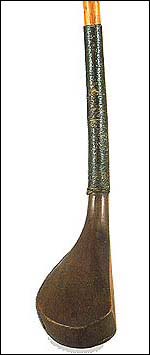

Middle Spoon

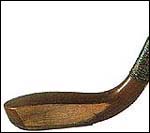

"Laidlay" Putter

This

genius made such beautiful and perfect wooden putters that he has come

to be regarded as the Amati or Stradivarius of Golf, and a genuine "Philp"

today is worth untold gold. The long narrow faces of these clubs and their

perfect balance are well known to connoisseurs (Golf Illustrated, 5 Oct.

1900: 12).

This

genius made such beautiful and perfect wooden putters that he has come

to be regarded as the Amati or Stradivarius of Golf, and a genuine "Philp"

today is worth untold gold. The long narrow faces of these clubs and their

perfect balance are well known to connoisseurs (Golf Illustrated, 5 Oct.

1900: 12).

It was Hugh Philp who first departed from the

primitive models of the stone age and began to make golf clubs that looked

as though they were intended for some gentler work than the crushing in

of an enemy's skull or the manufacture of broken flint for road-building.

Philp had an eye for graceful lines and curves, and his slim, elegant models

remain today things of beauty . . . . Moreover, as any fine crusted golfer

will tell you, Philp was the only man who ever knew how to make a perfectly

balanced wooden putter. The few specimens that still exist are acknowledged

"old masters," and are only to be exchanged against much fine gold (Harper's

Weekly, 2 Oct. 1897: 986).

Ever since his death in 1856, Hugh Philp has been universally

recognized as clubmaking's finest artisan. His clubs have been copied and

even forged, complete with his name. Philp's clubs were collectible 100

years ago. During the 1890s, a few people actually advertised in Golf,

a weekly periodical, offering to purchase his work at prices well above

the cost of any new club. His craftsmanship was often compared to that

of legendary and fabled violin maker Antonio Stradivari. Even a few aluminum

head putters made in the early 1900s were modeled after Philp's designs.

Philp was more than a talented clubmaker. His reputation

for being meticulous was legend:

Philp, in the olden times, was in the

wont of spending half a day agreeably putting the finishing touches to

a club after it had been handed over by his workmen as completed (The Golfer,

3 Nov. 1894: 184).

Today, Hugh Philp's legacy continues unabated. He is

considered the premier long nose clubmaker. He set the standard by which

the work of other clubmakers is measured. Decent examples of his clubs

are cherished.

The 42-inch long spoon pictured on the facing page

measures 5 3/4 inches in head length, 1 7/8 inches in width, and 1 inch

in face depth. Formerly owned by the Arbroath Golf Club, in Arbroath, Scotland,

this nearly unused example was displayed in their clubhouse for years before

being sold, to raise funds, in the early 1980s.

Because Hugh Philp's clubs have been highly sought

after ever since his death, many examples remain. Approximately 190 are

known. The opportunity to obtain a nice Philp is, in many ways, rarer than

the club itself. Many examples are held by golf organizations ranging from

the R&A and the USGA to such venerable clubs as The Honorable Company

of Edinburgh Golfers (Muirfield) in Scotland and the Los Angeles Country

Club. The remaining examples are primarily in the hands of serious collectors.

Therefore, a Philp in nice condition rarely becomes available.

The 42-inch Philp long spoon pictured on this page

is one of only five known examples marked "H. Philp" in script. Robert

Davidson routinely stamped his clubs in script, and Tom Hood stamped a

large percentage of his clubs in script, but Philp stamped only a few of

his clubs that way. It is thought that Philp used his script stamp to identify

either his personal clubs or the presentation clubs he made for a particular

person or occasion. This particular script-stamped clubhead measures 5

1/2 inches long, 2 inches wide, and 1 inch in face depth.

In 1899 a letter requesting information about Hugh

Philp was sent to the editor of Golf. The response came from the hand of

none other than Robert Forgan, the successor to Philp's business and one

of Philp's two former assistants. (In addition, Robert Forgan was related

to Hugh Philp through Forgan's marriage to the daughter of James Berwick,

Philp's brother-in-law.) Forgan's letter reads in part as follows:

Hugh Philp died April 6, 1856, in his

seventy-fourth year. He served no apprenticeship to club-making, but was

bred to the trade of joiner and house carpenter. He carried on that business

in Argyle Street, St. Andrews; and as there were no club makers in St.

Andrews at that time, the golfers began to take their clubs to him to be

repaired; and after a time they got him to come down to the links where

he had a shop where the Grand Hotel is now built. That would be somewhere

between 1820 and 1825 [during September of 1819 Philp was appointed official

clubmaker to the Society of Golfers at St. Andrews]. Some few years after

that he bought the property now occupied by Tom Morris, where he died in

1856. I don't know where he was born, nor how long he made clubs, but I

have heard him say that he made them for over fifty years. I was his assistant

when he died-his former assistant having left him in 1852 and opened a

club maker's shop on the ground where the Marine Hotel is now built. His

name was James Wilson, and was twenty- three years Mr. Philp's assistant.

[Andrew Strath was also an apprentice to Philp (Tulloch 1908, 22).] I was

four years Mr. Philp's assistant, and I succeeded to the business which

is now carried on under the name of R. Forgan and Son (Golf, 3 Feb. 1899:

412).

A few putters stamped both "Forgan" and "Philp" are known. In the past,

these clubs were believed to signify the result of a business partnership

during Philp's lifetime. This is not correct. These clubs were made by

Robert Forgan & Son years after Philp's death, out of respect for the

inheritance of Philp's business and the continued popularity of Philp's

clubs, especially his putters. It was also good business for Forgan to

remain linked to Philp. Philp/Forgan putters were produced briefly during

the 1890s as indicated by their fork splice and awkward head shape which

does not begin to resemble anything made by the master himself. Also, the

"H. Philp" lettering stamped on those clubs is unlike anything found on

a genuine Philp. Although recently reshafted and rewhipped, the circa 1850

Philp clubhead on this page is a solid example. Its lines are graceful

and elegant, and Philp's original finish remains untouched. A wonderful

article recalling Hugh Philp, originally cited as from "Chambers Journal,

1859," was reprinted in 1899. Titled "Hugh Philp The Master," it provides

an illuminating glimpse into his daily life. It reads in part:

A few putters stamped both "Forgan" and "Philp" are known. In the past,

these clubs were believed to signify the result of a business partnership

during Philp's lifetime. This is not correct. These clubs were made by

Robert Forgan & Son years after Philp's death, out of respect for the

inheritance of Philp's business and the continued popularity of Philp's

clubs, especially his putters. It was also good business for Forgan to

remain linked to Philp. Philp/Forgan putters were produced briefly during

the 1890s as indicated by their fork splice and awkward head shape which

does not begin to resemble anything made by the master himself. Also, the

"H. Philp" lettering stamped on those clubs is unlike anything found on

a genuine Philp. Although recently reshafted and rewhipped, the circa 1850

Philp clubhead on this page is a solid example. Its lines are graceful

and elegant, and Philp's original finish remains untouched. A wonderful

article recalling Hugh Philp, originally cited as from "Chambers Journal,

1859," was reprinted in 1899. Titled "Hugh Philp The Master," it provides

an illuminating glimpse into his daily life. It reads in part:

Could the past be relived, you might

enter Hugh's shop with me; as it is, do so in fancy. It is not a very commodious

habitation, being a small square box erected on the convenient brink of

the course at the commencement of the links. Round the walls are ranged

boxes filled with finished clubs for the golfer to choose from; piles of

embryo handles and heads, and quantities of doubtful material, yet undeveloped,

strew the ground; overhead are horizontal racks of clubs belonging to some

of Hugh's customers, who claim a kind of prescriptive right to keep their

sets in his shop; and in one corner is Hugh's own particular bench. The

shop is evidently a place where golfers of all descriptions . . . congregate;

caddies waiting engagements, gentlemen players smoking their pipes, chatting

with Hugh, or selecting their clubs. Hugh himself is polishing and stamping

his name on some clubheads. For many and many a year to come these letters

which he is branding on the clubs will serve for Hugh's best epitaph, and

golfers yet to be will sigh for the 'touch of that vanished hand' which

fashioned so deftly and so well. He is clad in his invariable snuff-colored

garb, and his silver-rimmed spectacles are pushed upward on his brow. His

keen black eye is glittering with the fun of some golfing story he has

been relating to a group of players. Hugh had plenty of these tales, and

told them with a dry comicality which was irresistible. But you should

have seen Hugh play a match. As a rule, he did not much care about leaving

his shop to play regular matches with gentlemen golfers, but occasionally

took a round when the chances were a little in his favour. Hugh thoroughly

understood both the etiquette and saving policy of the game, and never

if possible took his match before the burn hole, which left only one hole

more to play. He could, therefore, with every degree of plausibility, solace

his beaten opponent with the idea that it was a very, very close match-indeed,

that there was no saying how the next might go. . . . (Golfing, 16 Nov.:

24).

The exquisite Philp putter pictured here was once part of an unused set

of nine Philp clubs presented by Sir Hew Dalrymple, Bart., of Luchie, to

John E. Laidlay, a two-time British Amateur Champion and runner-up in the

1893 British Open. Recognized as a one of a kind, Laidlay's set of nine

Philps was displayed, at the request of the Reverend John Kerr, at the

Glasgow International Exhibition of 1901. It was also at Reverend Kerr's

suggestion that the archaeology committee of the Glasgow International

Exhibition included an exhibit on golf. In return, the committee put Kerr

in charge of preparing the display. The Glasgow International Exhibition

of 1901 opened in May and ran for six months. To allay the fears of lenders,

their golf treasures were housed in an isolated, fireproof structure, lighted

throughout by electricity and guarded day and night. (Upon completion of

the exhibition, the structure was to remain as a permanent art gallery

and museum.) Within this grand building the "Laidlay" Philp clubs were

displayed in their own special case. It was recognized, even then, that

Laidlay's Philps were of greater significance than the normal relic. In

1981 John Laidlay's set of Philp clubs was broken up-each club was sold

individually at a Sotheby's golf auction in London, England. The certificate

the Glasgow International Exhibition presented to Laidlay for lending his

clubs was auctioned as the lot following the last of the nine Philps. It

is believed that Laidlay's Philps were crafted in the early 1850s with

the aid of Philp's assistant, Robert Forgan. Such nine club sets were known

to be awarded as "prize clubs" to the winner of a competition (see Smith

1867, 11 & 18). Although this putter has never been used, the lead

in the back of the head has shifted slightly. This is not an unusual phenomenon

and can occasionally be found in other clubs. The head on this Philp putter

measures 5 3/4 inches long, 2 1/8 inches wide, and only 15/16 of an inch

in face depth.

The exquisite Philp putter pictured here was once part of an unused set

of nine Philp clubs presented by Sir Hew Dalrymple, Bart., of Luchie, to

John E. Laidlay, a two-time British Amateur Champion and runner-up in the

1893 British Open. Recognized as a one of a kind, Laidlay's set of nine

Philps was displayed, at the request of the Reverend John Kerr, at the

Glasgow International Exhibition of 1901. It was also at Reverend Kerr's

suggestion that the archaeology committee of the Glasgow International

Exhibition included an exhibit on golf. In return, the committee put Kerr

in charge of preparing the display. The Glasgow International Exhibition

of 1901 opened in May and ran for six months. To allay the fears of lenders,

their golf treasures were housed in an isolated, fireproof structure, lighted

throughout by electricity and guarded day and night. (Upon completion of

the exhibition, the structure was to remain as a permanent art gallery

and museum.) Within this grand building the "Laidlay" Philp clubs were

displayed in their own special case. It was recognized, even then, that

Laidlay's Philps were of greater significance than the normal relic. In

1981 John Laidlay's set of Philp clubs was broken up-each club was sold

individually at a Sotheby's golf auction in London, England. The certificate

the Glasgow International Exhibition presented to Laidlay for lending his

clubs was auctioned as the lot following the last of the nine Philps. It

is believed that Laidlay's Philps were crafted in the early 1850s with

the aid of Philp's assistant, Robert Forgan. Such nine club sets were known

to be awarded as "prize clubs" to the winner of a competition (see Smith

1867, 11 & 18). Although this putter has never been used, the lead

in the back of the head has shifted slightly. This is not an unusual phenomenon

and can occasionally be found in other clubs. The head on this Philp putter

measures 5 3/4 inches long, 2 1/8 inches wide, and only 15/16 of an inch

in face depth.

(This web layout does not follow the book layout. Locations

and quality of clubs do not match the highly detailed printed pages.)

This

genius made such beautiful and perfect wooden putters that he has come

to be regarded as the Amati or Stradivarius of Golf, and a genuine "Philp"

today is worth untold gold. The long narrow faces of these clubs and their

perfect balance are well known to connoisseurs (Golf Illustrated, 5 Oct.

1900: 12).

This

genius made such beautiful and perfect wooden putters that he has come

to be regarded as the Amati or Stradivarius of Golf, and a genuine "Philp"

today is worth untold gold. The long narrow faces of these clubs and their

perfect balance are well known to connoisseurs (Golf Illustrated, 5 Oct.

1900: 12).

A few putters stamped both "Forgan" and "Philp" are known. In the past,

these clubs were believed to signify the result of a business partnership

during Philp's lifetime. This is not correct. These clubs were made by

Robert Forgan & Son years after Philp's death, out of respect for the

inheritance of Philp's business and the continued popularity of Philp's

clubs, especially his putters. It was also good business for Forgan to

remain linked to Philp. Philp/Forgan putters were produced briefly during

the 1890s as indicated by their fork splice and awkward head shape which

does not begin to resemble anything made by the master himself. Also, the

"H. Philp" lettering stamped on those clubs is unlike anything found on

a genuine Philp. Although recently reshafted and rewhipped, the circa 1850

Philp clubhead on this page is a solid example. Its lines are graceful

and elegant, and Philp's original finish remains untouched. A wonderful

article recalling Hugh Philp, originally cited as from "Chambers Journal,

1859," was reprinted in 1899. Titled "Hugh Philp The Master," it provides

an illuminating glimpse into his daily life. It reads in part:

A few putters stamped both "Forgan" and "Philp" are known. In the past,

these clubs were believed to signify the result of a business partnership

during Philp's lifetime. This is not correct. These clubs were made by

Robert Forgan & Son years after Philp's death, out of respect for the

inheritance of Philp's business and the continued popularity of Philp's

clubs, especially his putters. It was also good business for Forgan to

remain linked to Philp. Philp/Forgan putters were produced briefly during

the 1890s as indicated by their fork splice and awkward head shape which

does not begin to resemble anything made by the master himself. Also, the

"H. Philp" lettering stamped on those clubs is unlike anything found on

a genuine Philp. Although recently reshafted and rewhipped, the circa 1850

Philp clubhead on this page is a solid example. Its lines are graceful

and elegant, and Philp's original finish remains untouched. A wonderful

article recalling Hugh Philp, originally cited as from "Chambers Journal,

1859," was reprinted in 1899. Titled "Hugh Philp The Master," it provides

an illuminating glimpse into his daily life. It reads in part:

The exquisite Philp putter pictured here was once part of an unused set

of nine Philp clubs presented by Sir Hew Dalrymple, Bart., of Luchie, to

John E. Laidlay, a two-time British Amateur Champion and runner-up in the

1893 British Open. Recognized as a one of a kind, Laidlay's set of nine

Philps was displayed, at the request of the Reverend John Kerr, at the

Glasgow International Exhibition of 1901. It was also at Reverend Kerr's

suggestion that the archaeology committee of the Glasgow International

Exhibition included an exhibit on golf. In return, the committee put Kerr

in charge of preparing the display. The Glasgow International Exhibition

of 1901 opened in May and ran for six months. To allay the fears of lenders,

their golf treasures were housed in an isolated, fireproof structure, lighted

throughout by electricity and guarded day and night. (Upon completion of

the exhibition, the structure was to remain as a permanent art gallery

and museum.) Within this grand building the "Laidlay" Philp clubs were

displayed in their own special case. It was recognized, even then, that

Laidlay's Philps were of greater significance than the normal relic. In

1981 John Laidlay's set of Philp clubs was broken up-each club was sold

individually at a Sotheby's golf auction in London, England. The certificate

the Glasgow International Exhibition presented to Laidlay for lending his

clubs was auctioned as the lot following the last of the nine Philps. It

is believed that Laidlay's Philps were crafted in the early 1850s with

the aid of Philp's assistant, Robert Forgan. Such nine club sets were known

to be awarded as "prize clubs" to the winner of a competition (see Smith

1867, 11 & 18). Although this putter has never been used, the lead

in the back of the head has shifted slightly. This is not an unusual phenomenon

and can occasionally be found in other clubs. The head on this Philp putter

measures 5 3/4 inches long, 2 1/8 inches wide, and only 15/16 of an inch

in face depth.

The exquisite Philp putter pictured here was once part of an unused set

of nine Philp clubs presented by Sir Hew Dalrymple, Bart., of Luchie, to

John E. Laidlay, a two-time British Amateur Champion and runner-up in the

1893 British Open. Recognized as a one of a kind, Laidlay's set of nine

Philps was displayed, at the request of the Reverend John Kerr, at the

Glasgow International Exhibition of 1901. It was also at Reverend Kerr's

suggestion that the archaeology committee of the Glasgow International

Exhibition included an exhibit on golf. In return, the committee put Kerr

in charge of preparing the display. The Glasgow International Exhibition

of 1901 opened in May and ran for six months. To allay the fears of lenders,

their golf treasures were housed in an isolated, fireproof structure, lighted

throughout by electricity and guarded day and night. (Upon completion of

the exhibition, the structure was to remain as a permanent art gallery

and museum.) Within this grand building the "Laidlay" Philp clubs were

displayed in their own special case. It was recognized, even then, that

Laidlay's Philps were of greater significance than the normal relic. In

1981 John Laidlay's set of Philp clubs was broken up-each club was sold

individually at a Sotheby's golf auction in London, England. The certificate

the Glasgow International Exhibition presented to Laidlay for lending his

clubs was auctioned as the lot following the last of the nine Philps. It

is believed that Laidlay's Philps were crafted in the early 1850s with

the aid of Philp's assistant, Robert Forgan. Such nine club sets were known

to be awarded as "prize clubs" to the winner of a competition (see Smith

1867, 11 & 18). Although this putter has never been used, the lead

in the back of the head has shifted slightly. This is not an unusual phenomenon

and can occasionally be found in other clubs. The head on this Philp putter

measures 5 3/4 inches long, 2 1/8 inches wide, and only 15/16 of an inch

in face depth.